Reflections from Behind Virtual Bars

What constitutes “hate speech” in 2022, idea pathogens, psychological immunity, and the freedom-versus-safety dichotomy

First, the facts:

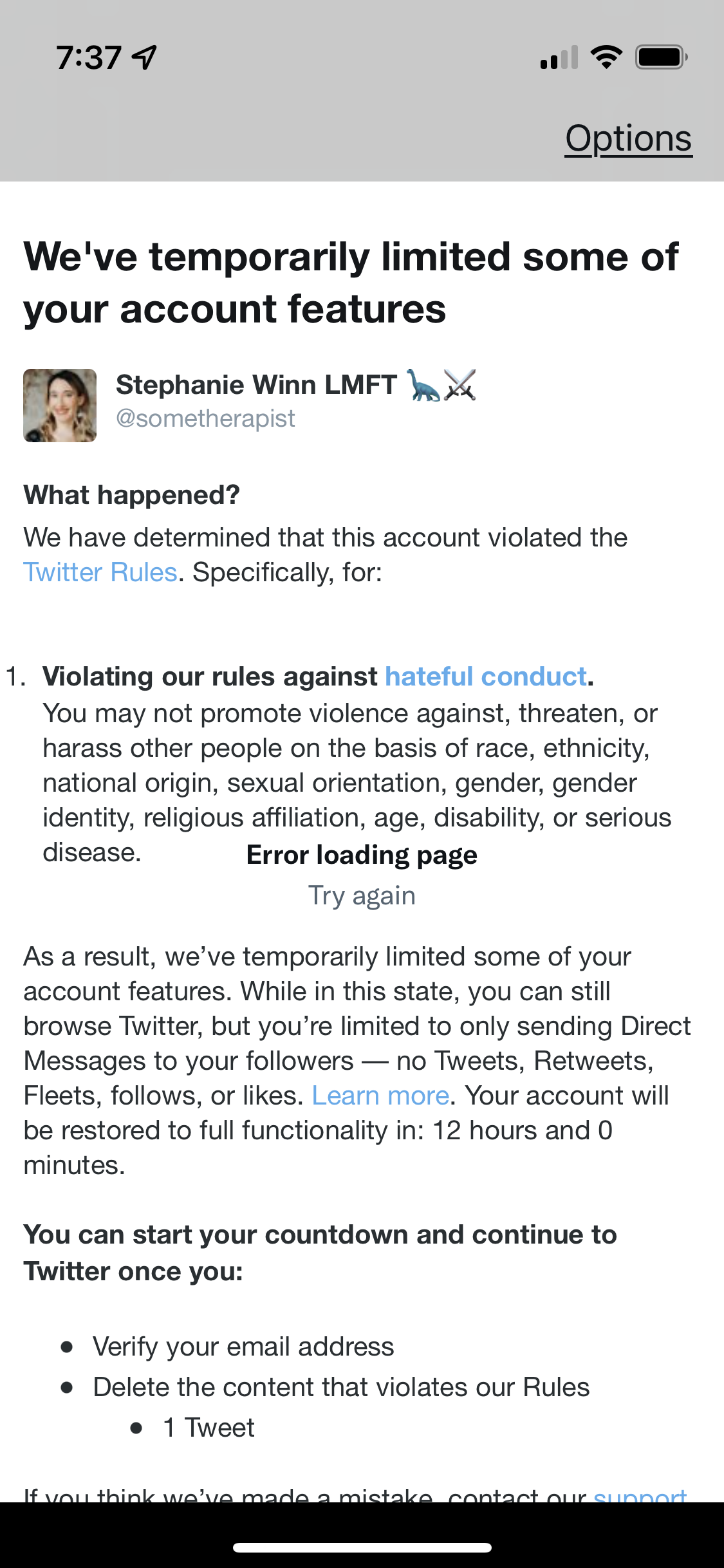

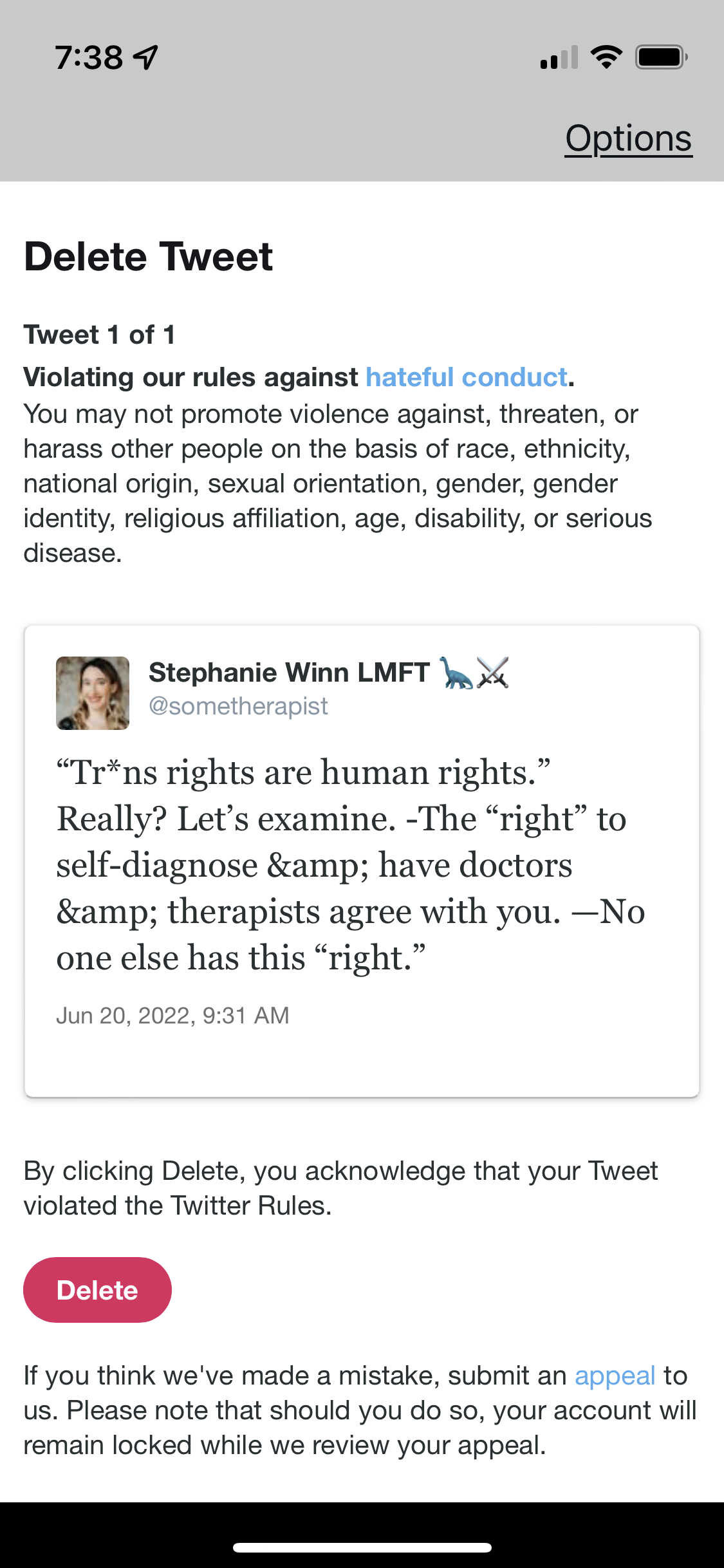

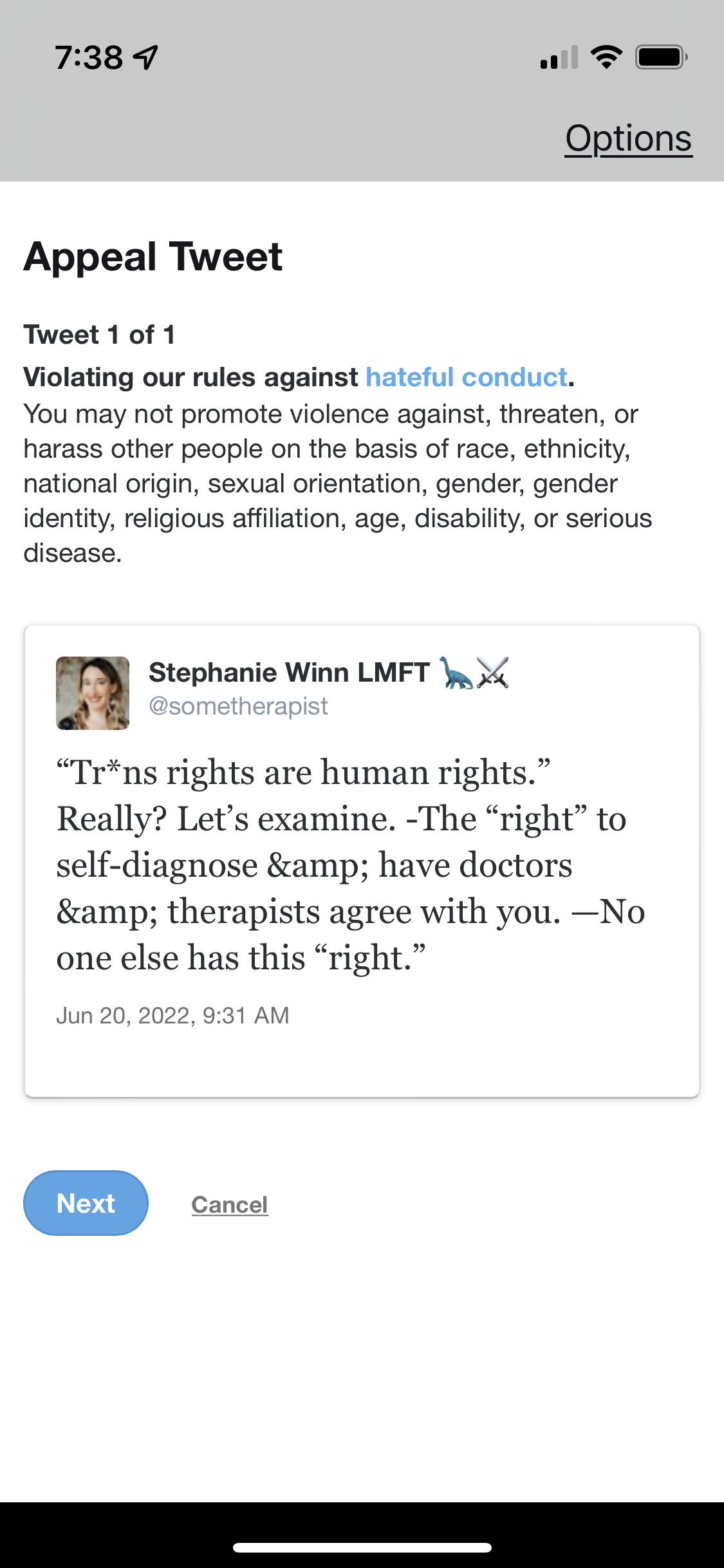

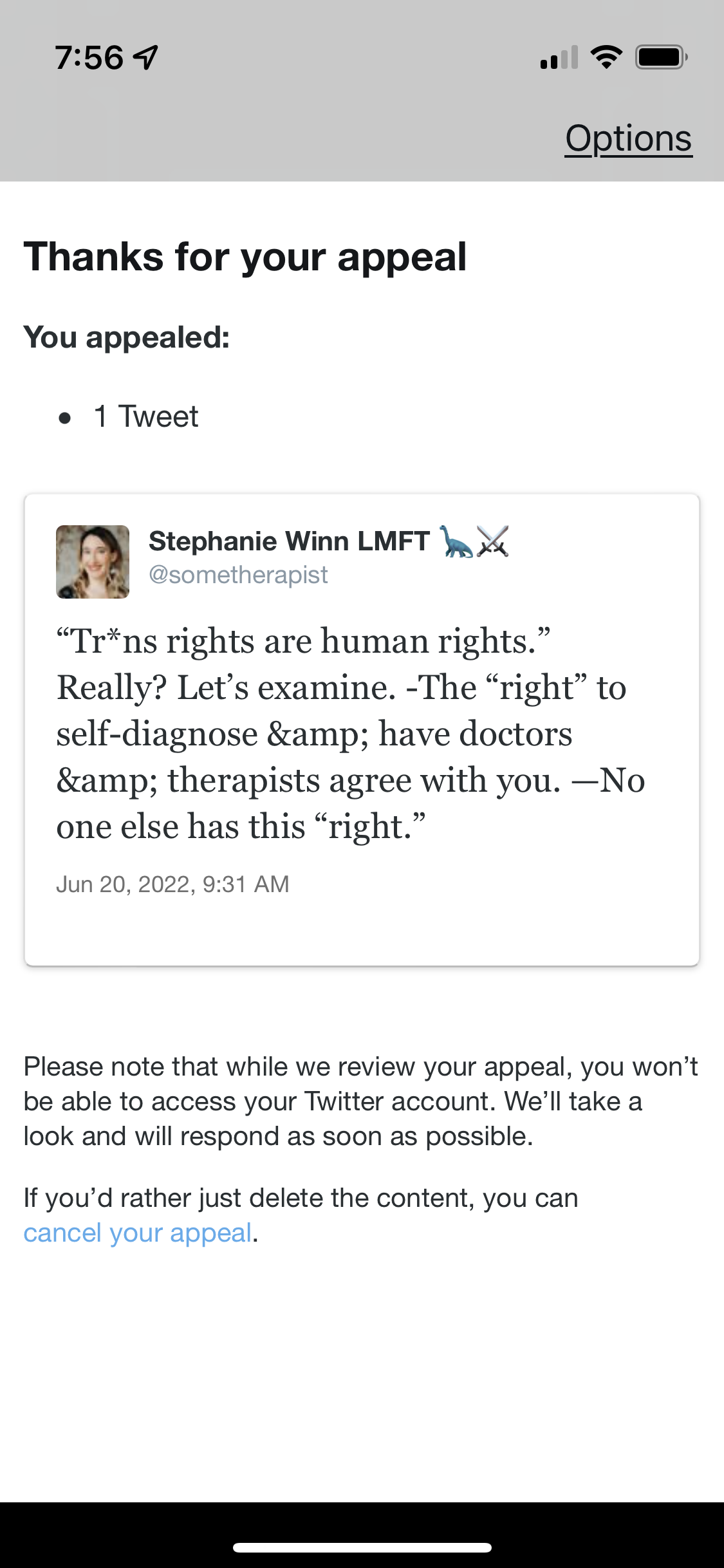

I’m locked out of my Twitter account, @sometherapist. This is what I encountered yesterday morning:

What happened and where things stand today: the boring details

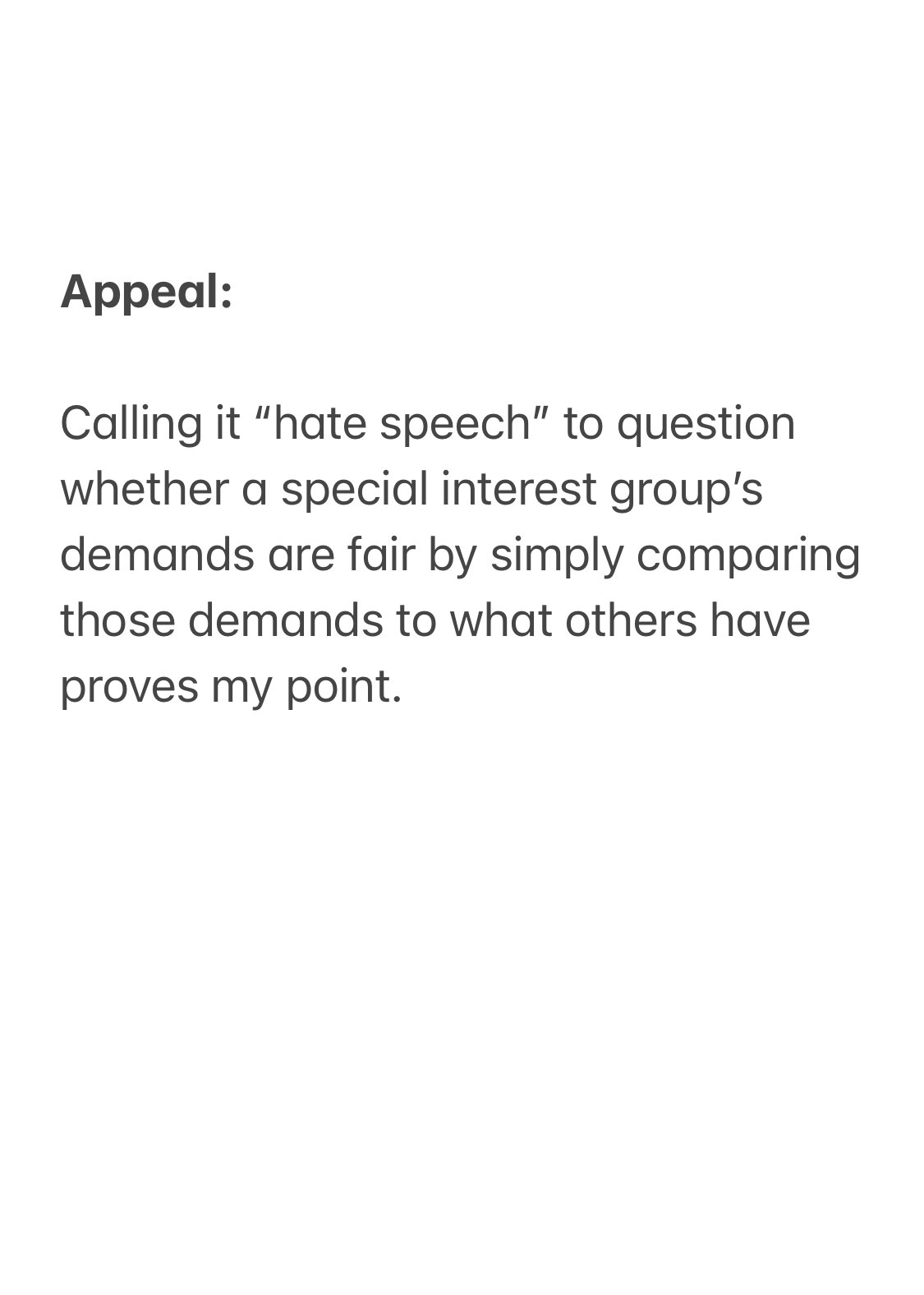

You might have to click through those pictures to see the offending tweet and how I appealed it.

Next, after submitting the appeal, I created a backup account, @some_therapist. It had occurred to me earlier in the day yesterday that I really should do this, just in case. Funny timing, that. As you can see, I made zero effort to hide my identity with this new account. I promptly shared what happened. Unfortunately, I seem to be “shadow banned” or “deboosted,” as a great many people have reported issues seeing this thread.

I went through the accounts my main account is following and followed them one after another in batches, a few times, each time until it told me I hit my limit, then returned a few minutes later. For a while, it just said “You are unable to follow more people at this time” briefly. Now, it still says that the next day, many hours later. I’m currently following 390 out of @sometherapist’s 1,212. These were not prioritized in any particular order; I was just going down the list in the order they appeared.

I reached out to several acquaintances via other channels, mainly Instagram and email, and asked them to spread the word. You might have heard about this through one of them. If I didn’t reach out to you but could have, please don’t take it personally. I only had about an hour to handle this yesterday morning, and just did whatever was top of mind.

So as of now, where things stand is that my new account has gained back just under 1k followers, of my primary account’s 7.2k+. Not a terrible number, all things considered. But without my original account, I’ll never get back my DMs or tweet history.

But perhaps most importantly, I’ll never get back my block list. I had been following a strategy I called, “block early and often.” Alphabet activists and their handmaidens, or for that matter anyone who engaged in abusive online behavior, was instantly blocked. I believe this habit spared me a lot of unnecessary stress. I am simply not online to engage with these kinds of people. Many of them pose risks of various kinds, not the least of which is, well, precisely what happened here. Without blocking in bulk, I might have been shut down a lot sooner.

Steel-manning the Devil’s Advocate on censorship

I’ll steel-man my opponent on one issue here. I can imagine the Devil’s Advocate calling it hypocritical for me to use the block feature, or perhaps even mute for some reason. To this point, I will say that a society that protects free speech also protects our right to walk away from what someone else is saying if we don’t like it and don’t feel like rebutting it, for whatever reasons, be they personal or political.

There are two main differences between me blocking a Twitter user, and Twitter itself blocking me from use. One is that I am an individual, not a corporation responsible for providing what basically amounts to a public utility. I’d rather pay for Twitter the same way I pay for Xfinity, and enjoy the same protections — knowing my internet won’t be shut down because some bureaucrat doesn’t like what I do with it — than use it for free, relying on it as the main virtual town square, only to be subject to this kind of baseless policing.

The second difference is that I am not trying to stop anyone from expressing themselves to others. I just want to choose who I allow to engage with me. When it comes to what others do, either I engage or I don’t. If I engage, I do my best to adhere to principles of minimum dignity: I argue with ideas, not people; use my most effective tools for reasoned debate; avoid name-calling or ad hominem attacks; strive for fairness and accuracy; monitor my thoughts and words for logical fallacies, cognitive distortions or manipulation tactics; choose my battles carefully; and take personal responsibility for managing my emotions. While I’m not perfect and have strayed from these on occasion, in general, if I can’t do this, or just don’t want to, I don’t engage. But I don’t try to stop others from engaging amongst themselves.

The same goes for my blog and YouTube channel. I monitor comments and retain the right to remove a comment or block a user from commenting. Why? Because it’s my space. My art project, in a way. Would I allow someone into my home if they were shouting obscenities and flailing their arms intimidatingly? No. I decide who I allow in. In general, all are welcome who behave respectfully. If people want to be disrespectful, they can go somewhere else. But something tells me that the kind of people who spend their time and energy criticizing others like this aren’t busy putting their energy to better use making their own original creations that they may curate as they like.

There are rare occasions where I find it appropriate to use social media reporting features. Here’s where I think we’re coming up against some crucial distinctions with very real consequences.

I use reporting when I see something as truly dangerous. Take “pro-ana thinspo,” for example. If you haven’t been exposed to this grim reality yet, in short, there’s a whole segment of social media, primarily Instagram, in which people, primarily adolescent girls and young women, share gruesome pictures and disturbing words actively promoting self-starvation. The dangers of this should be self-evident to anyone with half a brain: people are getting hurt. Eating disorders and the contagious concepts surrounding them are highly contagious mental diseases that should be quarantined because of their potential to infect and physically harm children. You wouldn’t send someone with a compromised immune system into a room full of Covid patients. Why would you send an insecure teen girl into a virtual room full of anorexics?

If anything, my ethics would compel me to want more censorship of material promoting self-harm on the internet. Gender ideology and other forms of hysterical obsession with self-diagnosis are near the top of that list. This leads us to some very important questions, though. I will explore the safety-versus-freedom dichotomy throughout the rest of this article.

Psychological germ theory

I am a mental health professional who views the health of the mind through a systems lens, and as not separate from the body. When we think of physical health, we think of factors an individual can control, such as sleep, nutrition, hydration, and exercise (or at least we should — if you don’t normally think of sleep as paramount with the latter, it’s time to adjust your priorities). We think of genetic risk factors for illness, and environmental factors such as exposure to pollutants. But we also consider germ theory and contagion. We understand that viruses, bacteria, and parasites can infect even the healthiest among us, and that these pathogens can spread through air, water, food, surfaces, touch, and/or sexual contact. We take various precautions to protect ourselves and one another. Since the pandemic hit, we’ve collectively engaged in a lot of fraught, anger and anxiety-fueled conflict with one another about the efficacy, benefits, risks, and costs of various approaches to limiting the spread of illness. But we all agree at least on the most basic principles that disease = bad and health = good. And we all understand that diseases spread exponentially between people in a population through various forms of exposure.

When it comes to mental health, I don’t believe our collective understanding has quite caught up with germ theory. We still view it through a highly individualistic lens. Only a relative few mavericks in the public eye — Gad Saad, Abigail Shrier, Lisa Littman come to mind — talk about idea pathogens via the spread of viral memes. I believe that the proportion of “mental illnesses” that are caused at least in part by contagious infections, rather than exclusively by genetic, environmental, or lifestyle factors, is much higher than we generally assume.

Ideas can cause health or disease. Diseases can be harmful, infecting and even killing people. In my estimation, self-sabotage, self-injury, self-starvation, addiction, and suicide may be more prevalent than violence and homicide. At least, they are certainly more treatable from a mental health standpoint. Sociopaths and psychopaths, people with Antisocial Personality Disorder, the sort who hurt and exploit others without remorse and sometimes even with glee, are notoriously resistant to most psychological interventions. They typically only attend counseling when court mandated, and can be skillful at saying whatever they need to say to complete “treatment” without any actual psychological change. Some who are brought to couples counseling by their abused partners, desperate for help, are able to outwit therapists and potentially make the situation worse. Sometimes there is no solution for people like this but to lock them up. In contrast, disorders in which a person turns against herself are much more amenable to treatment. Exposure to contagious, pathological ideas can play a huge role in internalizing, self-destructive mental illnesses, and this ought to be better studied.

If ideas can be dangerous, where do we go from here?

Here’s where my views start to coalesce with those of my ideological opponents. I think we actually agree on something: the idea that thoughts can be dangerous, and that some thought forms ought to be quarantined. This is why I speak out, and it’s why they attempt to silence me.

Because of how the political and ideological cards are currently stacked, we are so far from a world in which this is possible that it’s hard for me to imagine, but it’s worth asking myself: if I could quarantine ideas I consider to be dangerous, would I? In order to contemplate this question, I must reconcile dissonant concepts, reckoning my moral palate’s tastes for freedom and safety.

My need for freedom reels at the thought of trying to control anyone else’s speech or expression just as much as I resent the same being done to me. Whereas this drive feels idealistic in nature, my sense of safety feels more pragmatic in comparison. It’s not too different from how my longing for freedom wants me to go on a tropical vacation this winter, while my need for safety painfully reminds me of how I am still suffering the consequences of the Covid infection I contracted on my last trip to Mexico over four months ago. Or how just yesterday while out at a favorite park with my family, my sense of freedom wanted me to swim across the river, while my need for safety was concerned I wasn’t strong enough to navigate that particular combination of depth, current, and temperature. (We ended up finding a safer place to cross, a happy compromise between these essential drives.) These two driving needs for freedom and safety are quite frequently at odds with one another, and negotiating between the two is an ongoing balancing act for which one must gain at least a minimal degree of competence in order to navigate adulthood. Leaning too far into freedom at the expense of safety can lead to foolish and unnecessary loss of life, health, relationships, or financial security. Leaning too far into safety at the expense of freedom can leave a person trapped in a boring, stagnant, fear-based, mediocre existence.

This tense dichotomy is real. We all face it in our decision making processes, from the everyday and ephemeral to the profound and permanent. I won’t pretend otherwise.

So how do we effectively, wisely grapple with this dichotomy if ideas can be dangerous? How do we agree on which ideas are dangerous, assess their severity, and quarantine infections?

The mind — contained, so far as we know scientifically, within the nervous system (let’s leave metaphysical debates for another time) — is that faculty of the body that we use to make such decisions. And it is also, at the same time, the infected part. This presents a problem.

If you know you are battling Covid, then you can use your mind, impaired by brain fog as it may be, to help you make the best decisions possible. Contact your doctor, quarantine, rest, fluids, supplements, you know the drill. Your mind understands that your body is ill and you ought to be fighting it.

But what if you’ve been infected by an idea pathogen and you don’t know it?

Idea pathogens and the psychological immune system: the necessity of grappling with cognitive dissonance

Idea pathogens are more akin to clever parasites such as Toxoplasma gondii or Ophiocordyceps unilateralis, which affect the nervous systems and thus alter the behavior of the creatures they infect. Toxoplasma gondii is a pathogen cats pass along to rodents, inducing a condition called Toxoplasmosis, which alters rodents’ behavior such that they lose their innate, evolutionarily adaptive fear of cats and thus become easier targets as prey. This pathogen has also been shown to induce mood and behavior changes in some humans as well. Ophiocordyceps unilateralis, the cordyceps mushroom, is sometimes known as “the zombie-ant fungus,” as it takes over ants, controls their behavior and turns ants into vectors for transmitting more mushrooms at the expense of their own life. This is just a brief synopsis of my lay understanding of these two fascinating natural phenomena; I recommend doing your own research if these stories spark your interest. Suffice to say for the purpose of this article that there are parasitic pathogens in nature that cause infected organisms — that is, hosts — to turn against their own self-interest. Whereas evolution normally drives each living being to strive for its own survival and that of its offspring, some parasites’ unique way of expressing this drive for themselves inverts that very same drive’s expression in their hosts, all beneath the hosts’ conscious awareness. To whatever degree one could argue that rodents or ants are capable of “thought,” surely these creatures “think” they are continuing to act in their own self-interest, just as they always have, even as they unwittingly self-destruct for their hosts.

If we are willing to entertain the notion that idea parasites analogous to T. gondii or O. unilateralis exist in human minds, then we see it is possible to be infected unwittingly. In fact, mental pathogens depend on their ability to operate beneath the surface of conscious awareness. If we were conscious of them, we would fight them, just like being conscious of having an infection allows us to treat it. This is why I routinely assert that cultivating the ability to grapple with one’s own cognitive dissonance — precisely as I am modeling in this article by exploring the tension between the drives for freedom and safety — helps us grow. In particular, such an ability to reckon with inner dissonance inoculates us against infections from idea pathogens, strengthening our psychological immune systems, and thus bolstering our mental health. Being able to recognize when your thoughts, feelings, and actions do not align with one another, and harnessing the motivation to struggle internally until some inner coherence is once again reached, is akin to your white blood cells recognizing an invader that does not belong in your body and calling in the T-cell troops. (Or something of the sort. I’m no immunologist.)

Example: if you think of yourself as a compassionate person, yet find yourself calling someone names and attempting to destroy their reputation, you might be infected with a mind-virus that has caused you to act against your own self-interest; that is, your dignity and integrity. If you can catch this disconnect and examine it — “huh, that’s not like me. Why am I doing that?” then you stand a chance at identifying and rooting out the source of the problem. By investigating the issue, you may discover that you have fallen prey to an ideology that has exploited your compassion and used it against you via a series of complex, bizarre narratives that had momentarily hypnotized and seduced you into believing that Group X is full of victims who are being persecuted by Group Y and the best way for you to express your value of compassion is to stamp out Group Y by any means possible, even hostile ones. You are then empowered to ask whether you know for certain that this is the truth and the best course of action, or whether something fishy may be going on. Is it possible Group Y is actually the victim, and you have been exploited by your own compassion to become a Flying Monkey handmaiden of Group X so that they can use you for ulterior motives you know nothing of? Perhaps; it’s worth investigating. You can assess the situation for yourself and bring yourself back into alignment so that your beliefs, words and actions are once again in integrity. You know who you are and are living by your values once again — not by a facsimile of those values that the virus created in order to trick you into doing its bidding.

Grappling with cognitive dissonance is mental work. It requires thinking. Not daydreaming, not reacting, not assuming, not believing, but real, brain-calorie-burning, willpower-exerting thinking. I hope I have demonstrated how it is not only good for you, but necessary for health. But just like some of us never go to the gym, we don’t often do this kind of mental work if we don’t have to and haven’t developed a taste for it nor build up a habit around it. We live in a world full of instant gratification of both physical and mental varieties. To utter a cliche, social media makes this exponentially worse.

Returning to the question: where do we go from here?

Let’s presume, for the sake of the argument, that I’m on to something here and have introduced a useful conceptual framework. We presume, then, that millions of us are walking around with mind-viruses, unaware; have cognitive dissonance beneath the surface we haven’t become aware of enough to grapple with; and have been seduced by psychological parasites into acting against our own integrity. What then?

We still must return to the tension between freedom and safety. I’ve just elaborated it further, but we’re right where we started. Even in a society that collectively understands and agrees on the problem of certain physical viruses — namely, Covid — we’re by no means anywhere close to collective agreement on what to do about those viruses, what to speak of mental ones. The freedom-versus-safety contention is a real ongoing dilemma of our time. In the name of freedom, some people want to take risks that threaten other people’s sense of safety. In the name of safety, some people want to impose restrictions that threaten other people’s sense of freedom.

In the name of freedom, some people want to do things that others, like me, view as harmful to their own health, and they want the freedom to spread those ideas to other people, as well, which my side views as highly dangerous. In the name of safety, I sound alarm bells about these harms I think we should collectively try to contain and control. In the name of safety, my adversaries sound alarm bells about the harm they believe I pose, and try to contain and control me, stifling my freedom. And so it goes.

My critics want to silence me because my freedom of expression is viewed as a threat to their safety. This is part of what makes their ideology such a powerful parasite: deeming things “unsafe,” regardless of any objective measures of safety, is the quickest shortcut to controlling others’ freedom so that the pathology cannot be defended against by normal processes of psychological immunity.

We are thus each viewing the other in a similar way. My recognition of the mirror here doesn’t change my belief that I’m right, and my certitude is robust enough to acknowledge the parallels without fearing I’ve undermined my credibility. Part of how I have faith in my convictions is that I have examined these issues from every angle, grappled with my own cognitive dissonance, and discerned self (my own integrity) from invader (ideas that are not my own). I can feel a profound difference, in my body, mind, and behavior, between what it feels like to think and act on ideas that are not my own, which I have done numerous times in the past, and how it feels to think and act for myself.

How I know I’m infection-free

When I am thinking and acting for myself, I am clear-minded and mostly fearless, with occasional surges of adrenaline if something triggers a sense of being under attack. Not because the attack makes me uncertain of my ideas or my character, but because it makes me momentarily fear for my safety, reputation, or livelihood until I have assessed the situation and what, if any, real risks are being posed. When I am under the influence of an unquestioned idea, I am mentally hazier, with more free-floating anxiety, and any fear of attack that I experience makes me question my own essential goodness.

When I am thinking and acting independently, I find many people I mostly agree with and even some that I admire, but I can always find at least one point on which I disagree. When I am infected, something holds me back from disagreeing with those I view as being in the right; it’s as if that would make me a lesser person somehow. Similarly, when I am independent, I view people as my equals, feel comfortable expressing myself as a peer alongside those I admire, and have a clear and compassionate perspective toward those I see as off-course. In contrast, when my mind has been captured, I look up to some people and down upon others; feel far less comfortable approaching those I’ve idealized with my own ideas, because I sense I need their approval; and have a harder time with conflict.

I recently got to meet one of my heroes, Heather Heying. I was a bit nervous, but I was myself, and even found myself joking around. I am so grateful. I admire her and I can be myself around her. I cannot imagine feeling this way toward anyone I looked up to back when I was captured. Then again, hindsight being what it is, I question now whether I really did look up to anyone with the kind of genuine fondness I honestly feel toward Heather — that is, with something on the spectrum of love — or if my admiration stemmed more from a quiet fear, the sort one feels toward an intimidating authority figure, not altogether unlike what some may experience as the fear of God.

Are words violence?

“Words are violence.”

“Silence is violence.”

These are two mutually contradictory dictums of radical left ideology, one of several common pairings that together trap the adherent in a double-bind. In victim ideology, those in “oppressor” demographics can never do anything right, while those deemed “oppressed” can do no wrong. It’s no wonder so many people on the left thus opt-in to the one “oppressed” category a person can simply “identify as.”

Are either of these true… ever?

Maybe… yes and no? Not the way the leftists think, not in my opinion. But.

Thoughts can be contagious and destructive. The questions are,

Which thoughts?

How contagious and destructive are they? What makes them so?

And what, if anything, do we do about them?

I am in Twitter jail because someone thinks my thoughts are so contagious and destructive that they need to be quarantined to prevent them from infecting others. It’s my freedom versus their sense of safety, in their mind.

But hey, let’s be fair: those thoughts of mine that they think are so awful? Those thoughts are my judgments about how their ideas are contagious, destructive, and should be contained. In this regard, it’s my sense of safety versus their ideas of freedom.

I want to protect children from contagious ideology that has the potential to be incredibly destructive both physically and mentally. That’s how I think of my position. But it’s also how they think about theirs.

Just because I thoroughly believe I’m right and they’re wrong doesn’t mean that I’m unable or willing to see the situation from many angles, enough to acknowledge the above. I believe I must do so in order to be effective. I’m not fragile, and neither are my views.

So who is winning?

It’s hard to ascertain how the war is going from any given battlefield. At this moment, it appears I am losing this particular battle. That situation could change tomorrow; Twitter could respond to my appeal as desired and acknowledge that it is not “hate speech” to question whether a group’s demands really constitute basic “human rights” or special privileges. But they could also behave like a captured institution. I might find myself in the position of having to weigh the benefits of having my account back against the cost to my dignity of deleting the offending tweet and in so doing, acknowledging that it was so-called “hate speech.”

One thing I will tell you, though, is that my “When someone tries to chop your head off, be a Hydra and grow two more” approach hasn’t failed me yet.

Sometimes, losing a battle helps win the war.

What next?

One of my original intentions with this article was to attempt to recreate the original offending tweet and further elaborate on its concepts. I’ll have to do that another time, though. Hopefully soon. When I do, I’ll try to link back and forth between that article and this one. If you don’t see it, remind me.

I don’t know if and when I will get my account back, or what it will cost me, or how useful my new account will be. I’ll let you know when I know more.

I’d like to ask my audience to support me in a few ways. By engaging in more than one way of following me, you help ensure we won’t lose touch if this happens again or if this ban is permanent.

Follow my backup Twitter account, @some_therapist. Be aware you may not see all my content and it may be demoted.

Follow me on Instagram and Gettr @sometherapist. I’m not active on Gettr yet, but I could be.

Subscribe to my YouTube channel. Like, comment on, and share videos.

Follow, rate and review the show on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

Share the news of my silencing in a few different ways to help evade shadow banning. Encourage others to follow me in all these ways as well.